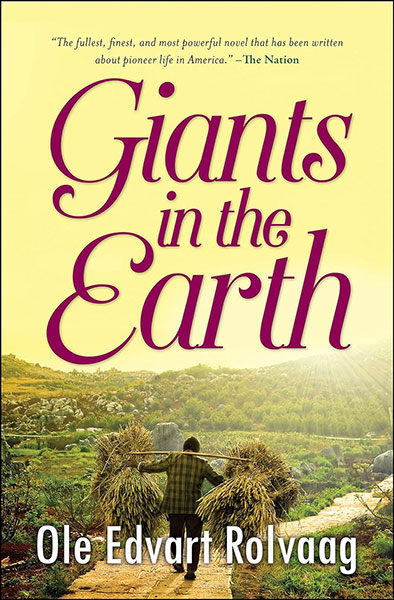

Giants in the Earth

Originally published in 1927, Ole Edvart Rolvaag's ‘Giants in the Earth’ is a classic Norweigian-American immigration novel. Ole Edvart Rolvaag was a Norwegian-American novelist and professor who became well known for his writings regarding the Norwegian American immigrant experience. ‘Giants in the Earth’ follows a Norwegian pioneer family's struggles with the land and the elements of the Dakota Territory as they try to make a new life in America. The book is based partly on Rolvaag's personal experiences as a settler, and on the experiences of his wife’s family who had been immigrant homesteaders. The novel depicts snowstorms, locusts, poverty, hunger, loneliness, homesickness, the difficulty of fitting into a new culture, and the estrangement of immigrant children who grow up in a new land. Giants in the Earth was turned into an opera by Douglas Moore and Arnold Sundgaard; it won the Pulitzer Prize for Music in 1951.

BEST DEALS

Read Sample

Chapter 1 : Toward the Sunset

I

Bright, clear sky over a plain so wide that the rim of the heavens cut down on it around the entire horizon. … Bright, clear sky, to-day, to-morrow, and for all time to come.

…And sun! And still more sun! It set the heavens afire every morning; it grew with the day to quivering golden light—then softened into all the shades of red and purple as evening fell. … Pure colour everywhere. A gust of wind, sweeping across the plain, threw into life waves of yellow and blue and green. Now and then a dead black wave would race over the scene … a cloud’s gliding shadow … now and then…

It was late afternoon. A small caravan was pushing its way through the tall grass. The track that it left behind was like the wake of a boat—except that instead of widening out astern it closed in again.

“Tish-ah!” said the grass… “Tish-ah, tish-ah!” … Never had it said anything else—never would it say anything else. It bent resiliently under the trampling feet; it did not break, but it complained aloud every time—for nothing like this had ever happened to it before… “Tish-ah, tish-ah!” it cried, and rose up in surprise to look at this rough, hard thing that had crushed it to the ground so rudely, and then moved on.

A stocky, broad-shouldered man walked at the head of the caravan. He seemed shorter than he really was, because of the tall grass around him and the broad-brimmed hat of coarse straw which he wore. A few steps behind him followed a boy of about nine years of age. The boy’s blond hair was clearly marked against his brown, sunburnt neck; but the man’s hair and neck were of exactly the same shade of brown. From the looks of these two, and still more from their gait, it was easy to guess that here walked father and son.

Behind them a team of oxen jogged along; the oxen were drawing a vehicle which once upon a time might have been a wagon, but which now, on account of its many and grave infirmities, ought long since to have been consigned to the scrap heap—exactly the place, in point of fact, where the man had picked it up. Over the wagon box long willow saplings had been bent, in the form of arches in a church chancel—six of them in all. On these arches, and tied down to the body on each side, were spread first of all two handwoven blankets, that might well have adorned the walls of some manor house in the olden times; on top of the blankets were thrown two sheepskin robes, with the wool side down, which were used for bed-coverings at night. The rear of the wagon was stowed full of numberless articles, all the way up to the top. A large immigrant chest at the bottom of the pile, very long and high, devoured a big share of the space; around and above it were piled household utensils, tools, implements, and all their clothing.

Hitched to this wagon and trailing behind was another vehicle, homemade and very curious-looking, so solidly and quaintly constructed that it might easily have won a place in any museum. Indeed, it appeared strong enough to stand all the jolting from the Atlantic to the Pacific… It, too, was a wagon, after a fashion; at least, it had been intended for such. The wheels were made from pieces of plank fitting roughly together; the box, considerably wider than that of the first wagon, was also loaded full of provisions and household gear, covered over with canvas and lashed down securely. Both wagons creaked and groaned loudly every time they bounced over a tussock or hove out of a hollow… “Squeak, squeak!” said the one… “Squeak, squeak!” answered the other… The strident sound broke the silence of centuries.

A short distance behind the wagons followed a brindle cow. The caravan moved so slowly that she occasionally had time to stop and snatch a few mouthfuls, though there was never a chance for many at a time. But what little she got in this way she sorely needed. She had been jogging along all day, swinging and switching her tail, the rudder of the caravan. Soon it would be night, and then her part of the work would come—to furnish milk for the evening porridge, for all the company up ahead.

Across the front end of the box of the first wagon lay a rough piece of plank. On the right side of this plank sat a woman with a white kerchief over her head, driving the oxen. Against her thigh rested the blond head of a little girl, who was stretched out on the plank and sleeping sweetly. Now and then the hand of the mother moved across the child’s face to chase away the mosquitoes, which had begun to gather as the sun lowered. On the left side of the plank, beyond the girl, sat a boy about seven years old—a well-grown lad, his skin deeply tanned, a certain clever, watchful gleam in his eyes. With hands folded over one knee, he looked straight ahead.

This was the caravan of Per Hansa, who with his family and all his earthly possessions was moving west from Fillmore County, Minnesota, to Dakota Territory. There he intended to take up land and build himself a home; he was going to do something remarkable out there, which should become known far and wide. No lack of opportunity in that country, he had been told! … Per Hansa himself strode ahead and laid out the course; the boy Ole, or Olamand, followed closely after, and explored it. Beret, the wife, drove the oxen and took care of little Anna Marie, pet-named And-Ongen (which means “The Duckling”), who was usually bubbling over with happiness. Hans Kristian, whose everyday name was Store-Hans (meaning “Big Hans,” to distinguish him from his godfather, who was also named Hans, but who, of course, was three times his size), sat there on the wagon, and saw to it that everyone attended to business… The cow Rosie trailed behind, swinging and switching her tail, following the caravan farther and farther yet into the endless vista of the plain.

“Tish-ah, tish-ah!” cried the grass… “Tish-ah, tish-ah!”…

II

The caravan seemed a miserably frail and Lilliputian thing as it crept over the boundless prairie toward the sky line. Of road or trail there lay not a trace ahead; as soon as the grass had straightened up again behind, no one could have told the direction from which it had come or whither it was bound. The whole train—Per Hansa with his wife and children, the oxen, the wagons, the cow, and all—might just as well have dropped down out of the sky. Nor was it at all impossible to imagine that they were trying to get back there again; their course was always the same—straight toward the west, straight toward the sky line…

Poverty-stricken, unspeakably forlorn, the caravan creaked along, advancing at a snail’s pace, deeper and deeper into a bluish-green infinity—on and on, and always farther on… It steered for Sunset Land!…

For more than three weeks now, and well into the fourth, this caravan had been crawling across the plain… Early in the journey it had passed through Blue Earth; it had left Chain Lakes behind; and one fine day it had crept into Jackson, on the Des Moines River. But that seemed ages ago… From Jackson, after a short lay-up, it had pushed on westward—always westward—to Worthington, then to Rock River… A little west of Rock River, Per Hansa had lost the trail completely. Since then he had not been able to find it again; at this moment he literally did not know where he was, nor how to get to the place he had to reach. But Split Rock Creek must lie out there somewhere in the sun; if he could only find that landmark, he could pick his way still farther without much trouble… Strange that he hadn’t reached Split Rock Creek before this time! According to his directions, he should have been there two or three days ago; but he hadn’t seen anything that even looked like the place… Oh, my God! If something didn’t turn up soon! … My God!…

The wagons creaked and groaned. Per Hansa’s eyes wandered over the plain. His bearded face swung constantly from side to side as he examined every inch of ground from the northeast to the southwest. At times he gave his whole attention to that part of the plain lying between him and the western sky line; with head bent forward and eyes fixed and searching, he would sniff the air, like an animal trying to find the scent. Every now and then he glanced at an old silver watch which he carried in his left hand; but his gaze would quickly wander off again, to take up its fruitless search of the empty horizon.

It was now nearing six o’clock. Since three in the afternoon he had been certain of his course; at that time he had taken his bearings by means of his watch and the sun… Out here one had to get one’s cross-bearings from the very day itself—then trust to luck…

For a long while the little company had been silent. Per Hansa turned halfway around, and without slackening his pace spoke to the boy walking behind.

“Go back and drive for a while now, Ola.… You must talk to mother, too, so that it won’t be so lonesome for her. And be sure to keep as sharp a lookout as you can.”

“I’m not tired yet!” said the boy, loath to leave the van.

“Go back, anyway! Maybe you’re not, but I can feel it beginning to tell on me. We’ll have to start cooking the porridge pretty soon. …You go back, and hold her on the sun for a while longer.”

“Do you think we’ll catch up with them to-night, Dad?” The boy was still undecided.

“Good Lord, no! They’ve got too long a start on us. … Look sharp, now! If you happen to see anything suspicious, sing out!” … Per Hansa glanced again at his watch, turned forward, and strode steadily onward.

Ole said no more; he stepped out of the track and stood there waiting till the train came up. Then Store-Hans jumped down nimbly, while the other climbed up and took his seat.

“Have you seen anything?” the mother asked in an anxious voice.

“Why, no … not yet,” answered the boy, evasively.

“I wonder if we shall ever see them again,” she said, as if speaking to herself, and looked down at the ground. “This seems to be taking us to the end of the world … beyond the end of the world!”

Store-Hans, who was still walking beside the wagon, heard what she said and looked up at her. The buoyancy of childhood shone in his brown face… Too bad that mother should be so scared!…

“Yes, Mother, but when we’re both steering for the sun, we’ll both land in the same place, won’t we? … The sun is a sure guide, you know!”

These were the very words which he had heard his father use the night before; now he repeated them. To Store-Hans the truth of them seemed as clear as the sun itself; in the first place, because dad had said it, and then because it sounded so reasonable.

He hurried up alongside his father and laid his hand in his—he always felt safer thus.

The two walked on side by side. Now and then the boy stole a glance at the face beside him, which was as stern and fixed as the prairie on which they were walking. He was anxious to talk, but couldn’t find anything to say that sounded grown-up enough; and so he kept quiet. At last, however, the silence grew too heavy for him to bear. He tried to say indifferently, just like his father:

“When I’m a man and have horses, I’m going to make a road over these plains, and … and put up some posts for people to follow. Don’t you think that’ll be a good idea?”

A slight chuckle came from the bearded face set toward the sun.

“Sure thing, Store-Hans—you’ll manage that all right. … I might find time to help you an hour or two, now and then.”

The boy knew by his father’s voice that he was in a talkative mood. This made him so glad, that he forgot himself and did something that his mother always objected to; he began to whistle, and tried to take just as long strides as his father. But he could only make the grass say: “Swish-sh, swish-sh!”

On and on they went, farther out toward Sunset Land—farther into the deep glow of the evening.

The mother had taken little Anna up in her lap and was now leaning backward as much as she could; it gave such relief to her tired muscles. The caresses of the child and her lively chatter made her forget for a moment care and anxiety, and that vague sense of the unknown which bore in on them so strongly from all directions… Ole sat there and drove like a full-grown man; by some means or other he managed to get more speed out of the oxen than the mother had done—she noticed this herself. His eyes were searching the prairie far and near.

Out on the sky line the huge plain now began to swell and rise, almost as if an abscess were forming under the skin of the earth. Although this elevation lay somewhat out of his course, Per Hansa swung over and held straight toward the highest part of it.

The afternoon breeze lulled, and finally dropped off altogether. The sun, whose golden lustre had faded imperceptibly into a reddish hue, shone now with a dull light, yet strong and clear; in a short while, deeper tones of violet began to creep across the red. The great ball grew enormous; it retreated farther and farther into the empty reaches of the western sky; then it sank suddenly… The spell of evening quickly crowded in and laid hold of them all; the oxen wagged their ears; Rosie lifted her voice in a long moo, which died out slowly in the great stillness. At the moment when the sun closed his eye, the vastness of the plain seemed to rise up on every hand—and suddenly the landscape had grown desolate; something bleak and cold had come into the silence, filling it with terror. … Behind them, along the way they had come, the plain lay dark green and lifeless, under the gathering shadow of the dim, purple sky.

Ole sat motionless at his mother’s side. The falling of evening had made such a deep impression on him that his throat felt dry; he wanted to express some of the emotions that overwhelmed him, but only choked when he tried.

“Did you ever see anything so beautiful!” he whispered at last, and gave a heavy sigh. … Low down in the northwest, above the little hill, a few fleecy clouds hovered, betokening fair weather; now they were fringed with shining gold, which glowed with a mellow light. As if they had no weight, they floated lightly there…

The mother drew herself forward to an upright position. She still held the child in her lap. Per Hansa and Store-Hans were walking in the dusk far up ahead. For the last two days Per had kept well in advance of the caravan all the time; she thought she knew the reason why.

“Per,” she called out, wearily, “aren’t we going to stop soon?”

“Pretty soon.” … He did not slacken his pace.

She shifted the child over into the other arm and began to weep silently. Ole saw it, but pretended not to notice, though he had to swallow big lumps that were forcing themselves up in his throat; he kept his eyes resolutely fixed on the scene ahead.

“Dad,” he shouted after a while, “I see a wood over there to the westward!”

“You do, do you? A great fellow you are! Store-Hans and I have seen that for a long time now.”

“Whereabouts is it?” whispered Store-Hans, eagerly.

“It begins down there on the slope to the left, and then goes around on the other side,” said his father. “Anyway, it doesn’t seem to be much of a wood.”

“D’you think they are there?”

“Not on your life! But we’re keeping the right course, anyhow.”

“Have the others been this way?”

“Of course they have—somewhere near, at any rate. There’s supposed to be a creek around here, by the name of Split Rock Creek, or whatever they call it in English.”

“Are there any people here, do you think?”

“People? Good Lord, no! There isn’t a soul around these parts.”

The sombre blue haze was now closing rapidly in on the caravan. One sensed the night near at hand; it breathed a chill as it came.

At last Per Hansa halted. “Well, I suppose we can’t drive any farther to-day. We and the animals would both drop pretty soon.” With these words he faced the oxen, held his arms straight out like the horizontal beam of a cross, shouted a long-drawn “Whoa!”—and then the creaking stopped for that day.

III

The preparations for the night were soon made; each had his own task and was now well used to it. Store-Hans brought the wood; it lay strapped under the hind wagon and consisted of small logs and dry branches from the last thicket they had passed.

Ole got the fireplace ready. From the last wagon he brought out two iron rods, cleft in one end; these he drove into the ground and then went back to the wagon for a third rod, which he laid across the other two. It was also his duty to see that there was water enough in the keg, no matter where they happened to stop; for the rest of it, he was on hand to help his mother.

The father tended to the cattle. First he lifted the yoke off the oxen and turned them loose; then he milked Rosie and let her go also. After that he made up a bed for the whole family under the wagon.

While the mother waited for the pot to boil she set the table. She spread a home-woven blanket on the ground, laid a spoon for each one on it, placed a couple of bowls for the milk, and fetched the dishes for the porridge. Meanwhile she had to keep an eye on And-Ongen, who was toddling about in the grass nearby. The child stumbled, laughed, lay there a moment chattering to herself, then got up, only to trip on her skirt and tumble headlong again. Her prattling laughter rang on the evening air. Now and then the voice of the mother would mingle with it, warning the child not to stray too far.

Store-Hans was the first to get through with his task; he stood around awhile, but, finding nothing more to do, he strolled off westward. He was itching to know how far it was to the hill out there; it would be great fun to see what things looked like on the other side! … Now he started off in that direction. Perhaps he might come across the others? They surely must be somewhere. Just think, if he could only find them! He would yell and rush in on them like an Indian—and then they would be scared out of their senses! … He had gone quite far before he paused to look back. When he did so the sight sent a shiver over him; the wagons had shrunk to two small specks, away off on the floor of a huge, dusky room… I’d better hurry at once, he thought; mother will surely have the porridge ready by this time! His legs had already adopted the idea of their own accord. But thoughts of his mother and the porridge didn’t quite bring him all the feeling of safety he needed; he hunted through his mind for a few strains of a hymn, and sang them over and over in a high-pitched, breaking voice, until he had no more breath left to sing with… He didn’t feel entirely safe until the wagons had begun to assume their natural size once more.

The mother called to them that supper was ready. On the blanket stood two dishes of porridge—a large dish for the father and the two boys, a smaller one for the mother and And-Ongen. The evening milk was divided between two bowls, and set before them; Rosie, poor thing, was not giving much these days! The father said that he didn’t care for milk this evening, either; it had a tangy taste, he thought; and he drank water with his porridge. But when Ole also began to complain of the tangy taste and asked for water, the father grew stern and ordered him to go ahead and get that drop of milk down as quick as he could! There was nothing else on the table but milk and porridge.

Suddenly Ole and Store-Hans flared up in a quarrel; one blamed the other for eating too close to the edge, where the porridge was coolest. The father paused in his meal, listening to them a moment, then chuckled to himself. Taking his spoon and cutting three lines through the crust of the porridge, he quickly settled the matter between them.

“There you are! Here, Store-Hans, is your land; now take it and be satisfied. Ola, who is the biggest, gets another forty… Shut up your mouths, now, and eat!” Per Hansa himself got the smallest share that evening.

Aside from this outbreak it was quiet at the table. A spell of silence lay upon them and they were not able to throw it off… As soon as the father had eaten he licked his spoon carefully, wiped it off on his shirt sleeve, and threw it on the blanket. The boys did likewise as they finished; but And-Ongen wanted to tuck her spoon in her dress and keep it there till morning.

They sat around in the same silence after they were done. Then she who was the smallest of them repeated in a tiny voice:

“Thanks to Thee, Our Lord and Maker…

“Now I want to go to sleep in your lap!” she said, after the Amen. She climbed up into her mother’s lap and threw her arms around her neck.

“Oh, how quickly it grows dark out here!” the mother murmured.

Per Hansa gave a care-free shrug of his shoulders. “Well,” he said, dryly, “the sooner the day’s over, the sooner the next day comes!”

But now something seemed to be brewing back there over the prairie whence they had come. Up from the horizon swelled a supernatural light—a glow of pale yellow and transparent green, mingled with strange touches of red and gold. It spread upward as they watched; the colors deepened; the glow grew stronger, like the witching light of a fen fire.

All sat silently gazing. It was And-Ongen, hanging around her mother’s neck, who first found her voice.

“Oh, look! … She is coming up again!”

In solemn grandeur the moon swung up above the plain. She had been with them many nights now; but each time she seemed as wonderful a sight as ever. Tonight a hush fell on their spirits as they watched her rise—just as the scene had hushed them the evening before, far away to the eastward somewhere on the plain. The silvery beams grew stronger; the first pale fen fire began to shimmer and spread; slowly the light mellowed into a mist of green and yellow and blue. And-Ongen exclaimed that the moon was much bigger to-night; but it had seemed bigger the night before also. Store-Hans again solemnly told her the reason for it—that the moon had to grow, just as she did! This seemed to her quite logical; she turned to her mother and asked whether the moon had milk and porridge every evening, too.

Per Hansa had been sitting on the tongue of the wagon, smoking his pipe. Now he got up, knocked out the ashes carefully, put his pipe in his pocket, and wound up his watch. These duties done, he gave the order to turn in for the night.

A little while later they all lay under the quilts, gazing off into the opalescent glow. When the mother thought that the children had gone to sleep she asked, soberly:

“Do you suppose we’ll ever find the others again?”

“Oh yes—I’m sure of it … if they haven’t sunk through the ground!”

This was all Per Hansa said. He yawned once or twice, long and heavily, as if he were very sleepy, and turned away from her.

…And after that she said no more, either.

IV

Truth to tell, Per Hansa was not a bit sleepy. For a long while he lay wide awake, staring into the night. Although the evening had grown cool, sweat started out on his body from time to time, as thoughts which he could not banish persisted in his mind.

He had good reason to sweat, at all the things he was forced to lie there and remember. Nor was it only tonight that these heavy thoughts came to trouble him; it had been just the same all through the day, and last night, too, and the night before. And now, the moment he had lain down, they had seized upon him with renewed strength; he recalled keenly all the scruples and misgivings that had obsessed his wife before they had started out on this long journey—both those which had been spoken and those which had been left unsaid. The latter had been the worst; they had seemed to grow deeper and more tragic as he had kept prying into them in his clumsy way… But she wasn’t a bit stupid, that wife of his! As a matter of fact, she had more sense than most people. Indeed she had!

…No, it wasn’t a pleasant situation for Per Hansa, by any means. He had not seen a happy moment, day or night, since the mishap had struck them on the second afternoon this side of Jackson. There the first wagon had got stuck in a mud hole; in pulling it out they had wrecked it so hopelessly that he had been forced to put back to Jackson for repairs. Under the circumstances, it had seemed to him utterly senseless to hold up all the rest of the company four days. He simply wouldn’t listen to their waiting for him; for they had houses to build and fields to break, if they were to get anything into the ground this season. They must go on without him; he’d come along all right, in his own good time… So they had given him full instructions about the course he was to follow and the halting places where he was to stop for the night; it had all seemed so simple to him at the time. Then they had started on together—Tönseten, who knew the way, and Hans Olsa, and the two Solum boys. They all had horses and strong new wagons. They travelled fast, those fellows!…

If he only had paid some attention to Hans Olsa, who for a long while had insisted on waiting for him. But he had overruled all their objections; it was entirely his own doing that Hans Olsa and the others had gone on, leaving him behind.

But he soon had learned that it wasn’t so easy. Hadn’t he lost his way altogether the other day, in the midst of a fog and drizzling rain? Until late in the afternoon that day he hadn’t had the faintest idea what direction he was taking. It had been after this experience that he had formed the habit of keeping so far ahead of the caravan. He simply couldn’t endure listening to her constant questions—questions which he found himself unable to answer…

The only thing he felt sure of was that he wasn’t on the right track; otherwise he would have come across the traces of their camps. It was getting to be a matter of life and death to him to find the trail—and find it soon… A devil of a jaunt it would be to the Pacific Ocean—the wagon would never hold out that long! … Oh yes, he realized it all too well—a matter of life and death. There weren’t many supplies left in the wagon. He had depended on his old comrade and Lofot-man, Hans Olsa, for everything.

Per Hansa heaved a deep sigh; it came out before he could stop it… Huh!—it was an easy matter enough for Hans Olsa! He had ample means, and could start out on a big scale from the beginning; he had a wife in whose heart there wasn’t a speck of fear! … The Lord only knew where they were now—whether they were east or west of him! And they had Tönseten, too, and his wife Kjersti, both of them used to America. Why, they could talk the language and everything…

And then there were the Solum boys, who had actually been born in this country… Indeed, east or west, it made no difference to them where they lay that night.

But here was he, the newcomer, who owned nothing and knew nothing, groping about with his dear ones in the endless wilderness! … Beret had taken such a dislike to this journey, too—although in many ways she was the more sensible of the two… Well, he certainly had fixed up a nice mess for himself, and no mistake!

He wondered why he had ever left Fillmore County; as he lay there thinking it over, he couldn’t understand what had prompted him to do such a thing. He could easily have found a job there and stayed until his wife got up from childbed; then he could have moved west next spring. This had been what she had wanted, though she had never said it in so many words.

The quilt had grown oppressively heavy; he threw it aside… How long it took her to go to sleep to-night! Why wouldn’t she try to get as much rest as possible? Surely she knew that it would be another tough day tomorrow?…

…Just so that confounded wagon didn’t go to pieces again!…

V

The night wore on. The children slept quietly and peacefully. The mother also seemed to have found rest at last. Per Hansa thought that she was sound asleep; he began to move slowly away from her. He threw his hand over on the quilt between them as if making a motion in his sleep… No, she didn’t stir; he lay quiet for a while, then moved again. In so doing his hand happened to fall on that of Store-Hans; it was so chubby and round, that hand, so healthy and warm, and quite firm for the hand of only a child. Per Hansa lay still for a long time, holding the boy’s hand with a desperate earnestness… Slowly the troublesome thoughts seemed to lighten and lift; his courage ebbed back again; surely everything would come out all right in the end!

Little by little he slipped the quilt off, crept out of bed as quietly as a mouse, got into his trousers, and pulled on his shoes.

Outside, the misty sheen of the moonlight shimmered so brightly that it blinded him. Near at hand, the prairie was bathed in a flood of tarnished green; farther off the faint blue tones began to appear, merging gradually into the purple dimness that shrouded all the horizon.

Per Hansa looked for the North Star, found it, turned about until he had it over his right shoulder; then he glanced at his watch, took a few steps, hesitated, and looked back as if taking a bearing of the wagons and the star. The next moment he faced about resolutely, and hurried off westward.

It felt good to be moving again; he almost broke into a trot. There were the oxen, busily grazing; they needed to get their fill all right, poor devils! … Rosie lay closer to the wagons; his eyes had passed over her at first, a dark spot in the vague, deceptive light. The cow must have noticed the shadow gliding along so swiftly; she gave a long moo… This enraged Per Hansa; he broke into a run and got out of her sight as quickly as he could, for fear she would moo again… If she only hadn’t waked Beret!

He set his course toward the point where he thought the crest of the ridge must lie. Now and then he stopped and looked around, to find out if he could still see the wagons. When he had lost them at last, and they were wholly swallowed up in the night, he gave an involuntary gasp—but clenched his teeth and went on.

The ridge lay farther off than he had thought. He had walked for a solid hour before he finally reached what he felt to be the highest point; he reckoned that he must be at least four miles from camp… There he fell to examining the ground carefully; but first of all he looked at his watch again, and then at the North Star and the moon, trying to fix the bearings of the camp in his mind.

On the other side of the ridge the lay of the land seemed to be different; the slope was a little steeper; a thick underbrush covered it; through the tall bushes the moonlight shimmered strangely… Per Hansa felt no fear, but every sense within him was alert. First he searched the northerly slope of the hill, beyond the edge of the thicket, stooping over as he went, his eyes scanning every foot of the ground. When he had found no trace of what he was looking for, he came back to the same starting point and searched an equal distance in the opposite direction; but he discovered nothing on this tack, either.

Now he began to walk along the edge of the thicket, in and out, crisscrossing the line in every direction; he pushed his way into each little grassless opening, and kicked over the earth there, before he went on. Sweat was running off him in streams. A quarter of an hour went by; he was still searching frantically… All at once, right at the edge of the woods, he struck a piece of level ground with a larger clearing on it; in the middle of this clearing lay a wide, round patch in the grass. Per Hansa threw himself down on his knees, like a miser who has found a costly treasure; he bent over and sniffed the ground. His blood throbbed; his hands shook as he dug… Yes, he was right—here there had been a fire! It couldn’t have been many days ago, either; the smell of the ashes was still fresh… His eyes had grown so moist and dim that he had to wipe them… But he wasn’t crying—no, not yet!…

He began to crawl around on all fours, farther and farther down the slope. Suddenly he stopped, sat up on his haunches, and held something in his hand that he was examining closely…

“I’ll be damned if it isn’t fresh horse dung!” … His voice rang with a great joy. He tried the stuff between his fingers—crumbled it, sniffed at it … there was no doubting the fact any longer.

Now he got up, walking erectly with a confident step, like a man who has just made a lucky strike, and began to search along the whole slope… He might as well go ahead and find the ford to-night; then he wouldn’t be delayed by hunting for it in the morning. The underbrush thickened as he made his way down the slope… Here, then, was Split Rock Creek; and here they had camped, as Tönseten had said they would!…

Once he had reached the edge of the creek, it did not take him long to find the ford that the others had used; the ruts still stood there plainly, as fresh and deep as if they had been made that very day. For a while he paused at the edge of the water, and looked about him… Had they chosen the best crossing, after all? The bank of the creek on the other side formed a bend; the brink looked pretty steep. At last he waded out into the water, with his shoes still on… Oh, well, the grade wasn’t so steep that the oxen couldn’t easily make it; there would be a bad jolt here at the edge, but after that they would have an even slope up the bank… Stepping out on the opposite shore, he stood as if rooted to the ground.

…“What in the devil…!”

Per Hansa bent over and picked up the object that lay before him; he held it out in the moonlight, turned it over and over in his hands, smelled of it … then took a bite.

…“By God! if it isn’t one of Hans Olsa’s dried mutton legs!”

He straightened himself up and gazed with deep thankfulness into the quivering bluish-green haze that glowed all around him… “Yes, that’s the way it goes, when people have more than they can take care of!” … He stuck the mutton leg under his arm; whistling a love ballad of Nordland, which seemed to have come into his mind unconsciously, he crossed the creek again.

On the way back he took his own time. Nothing mattered now; the night was fair and mild; his aching weariness was gone; he felt refreshed and strengthened. His wife and children were sleeping safe and sound; of food they still had supplies for a couple of weeks; and now he had found the trail again and could be certain of it all the way to Sioux Falls… That wretched wagon was the only difficulty; it would have to hang together for a few days more!…

When he drew near enough to the wagons to make them out clearly in the moonlight, he slackened his pace, and a shiver passed over him.

Wasn’t someone sitting there on the wagon tongue? Surely that was a human form?

In growing apprehension he hurried on.

“Good Heavens, Beret! What are you doing out here in the middle of the night?” His voice was full of alarm, yet softened by his great concern for her.

“It felt so awful to lie there alone, after you had gone… I could hardly breathe … so I got up.”

The words came with difficulty; he realized that her voice was hoarse with weeping; he had to pull himself sharply together in order to keep his own tears back.

“Were you awake, Beret? … You shouldn’t lie awake that way in the night!” he said, reproachfully.

“How can I sleep? … You lie there tossing back and forth, and say nothing! … You might have told me. I know very well what’s the matter!”

Suddenly she could stand it no longer. She ran over to him, flung her arms around his neck, and leaned close against him. The dam of her pent-up tears broke in a flood of emotion; she wept long and bitterly.

“Now calm yourself, dear… You must calm yourself, Beret-girl!” … He had put his arm lovingly around her, but found it hard to speak… “Don’t you see that I’ve got one of Hans Olsa’s dried mutton legs under my arm?”…

…That night Per Hansa was good to his wife.