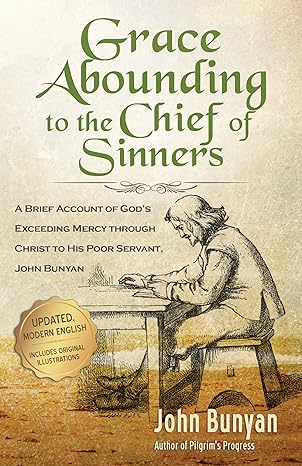

Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners - Updated, Illustrated

Come and hear, all ye that fear God, and I will declare what he has done unto my soul. (Psalm 66:16)

This is a short and honest account of how God demonstrated His exceeding great mercy to His unworthy servant, John Bunyan.

This story specifically tells how Bunyan was converted. John Bunyan was a companion of sin and was troubled by sin. He fought temptation and sin in his own strength and lost, and in despair he gave up hope of ever finding God’s mercy; but the Lord Jesus Christ at last delivered him from the guilt and terror that so often and so viciously troubled him.

In addition to this, a short account of Bunyan’s call to the work of the ministry is told, along with the trials and trouble he encountered – including some of the difficulties he faced while in prison.

This is all taken from his writings and is now published for the encouragement and support of others who are weak and tempted and need strength and hope and victory in Jesus.

BEST DEALS

About the Author

JOHN BUNYAN (1628-1688) was a Puritan preacher and writer in England. Bunyan had very little schooling. He followed his father in the tinker's trade, and served in the parliamentary army from 1644 to 1647. In 1655, Bunyan became a deacon and began preaching. He experienced marked success from the start and was the pastor of the Bedford church.

Bunyan is the author of The Pilgrim's Progress which he wrote in 1676 while imprisoned for preaching without a license. His numerous other titles include Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners and Holy War.

Read Sample

1 : A Brief Summary of the Life of John Bunyan by William Brock

John Bunyan was born sometime in the year 1628. His birthplace was Elstow in Bedfordshire, England a village not particularly romantic or picturesque. If the development of genius depended upon the influence of the grand or the beautiful in nature, young Bunyan did not have much hope. There are no mountains near Elstow, no cataracts or cascades, and no gorges or ravines. It is a land of wheat and barley a land that will provide adequately for hardworking people, but not land that will make them rich.

Of Bunyan's forefathers, history makes no mention. Even of his parents, hardly anything is known. The parish register contains no entry prior to his birth. One marriage is recorded after he was born, in addition to two births, two baptisms, and six burials. The family was destitute and average in many ways. Not only did his father have to obtain their daily bread by the sweat of his brow, but the occupation by which he did so was the lowest of the low. He was a tinker, repairing pots and pans and other metal items. He traveled from place to place about the region for employment, but lived in Elstow.

It occurred to him that some learning would be advantageous to his son. Although John's parents were impoverished and undistinguished, they saw no reason why John should grow up to be an impoverished and insignificant man. Education might improve his lot in life.

At nearby Bedford, there was a free school for the children of the poor. It pleased God to put into his parents' hearts to send him there to learn to read and write. John attended the school but did not excel. As he afterwards confessed, he learned but little, and he forgot the little that he had learned. He was soon taken from school, so that he might work with his father in the art and mystery of pots and pans.

John's ungodliness was as advanced as it was offensive. Few could equal him in cursing, swearing, lying, and blaspheming. He was the ringleader of the village immoralities a great sin-breeder, infecting all the youth of the neighborhood with all manner of youthful vanities. He cared nothing for Holy Scripture, preferring a ballad or the local news. He was a notorious violator of the whole law of God, except for the seventh commandment forbidding adultery, which he declared he had carefully obeyed. The desire was strong to take his fill of sin. He wanted to see what sins were yet to be committed and then hurry to commit those sins, lest he should die before he had gratified his desire.

In 1644, when Bunyan was about sixteen years old, he entered the army and took part in the conflict that was then raging between Parliament and the king. The probability is that he was a Royalist. The evidence is not conclusive, but his loyalty is so demonstrative that he would hardly have been in arms against his sovereign, while his references to the depravity of his comrades indicate association with the Cavaliers, or Royalists, rather than with the Roundheads, or followers of Cromwell and supporters of Parliament. Prince Rupert was his hero, not Oliver Cromwell.

Once in particular, he was in great danger. At the siege of Leicester, he was chosen to be among the soldiers who were to undertake an assault. Another man, though, obtained permission to go instead of Bunyan. Early in the attack, his substitute was shot with a musket ball and died. This incident greatly affected Bunyan, as it seemed to be a summons from the Lord to turn from the error of his ways. Nor was this the only summons. Several times before, he had been rescued from an untimely end. More than once he had been saved from drowning, when he was all but dead and gone.

These deliverances worked upon his soul. The goodness of God was leading him to repentance, but he resisted God's Spirit and became unhappy night and day. Fearful dreams and visions scared him. When creating a disturbance on the village green, he found himself frequently at his wits' end. God was angry with him. He was a doomed man.

To put these thoughts out of his mind, he plunged headlong into his old sins. He grew more and more rebellious against God, even neglecting his work so that he might have more time for his ungodliness and vice. Sometimes for days, he was destitute of bread to eat.

Some friends kindly pitied him and advised him, among other things, to marry. With a good wife he might do better and escape the ruin that was at hand. He took their advice, and it was his mercy to find a woman whose father was considered godly. Wise people might have pronounced the engagement reckless. Even friends must have thought it premature, for, to say nothing of other things that they lacked, they had neither dish nor spoon between them. It was a great venture to be approved, perhaps, when seeing the results, but certainly not to be recommended for imitation in the prospect of a married life.

The new Mrs. Bunyan was not altogether lacking in items of worth, however, for she brought her husband two books. One was The Practice of Piety by Lewis Bayly, and the other was Arthur Dent's The Plain Man's Pathway to Heaven. So degraded, however, had John become that he had lost the ability to read with any ease, and she had to help him repair the loss. Pleased with her devotion to him in marriage, he yielded to her entreaties and took kindly to his book. They read together, she adding wise comments as they proceeded, hoping to persuade John to become a religious man. Her childhood home had been such a happy one; how pleasant it would be if her married home could be happy too! There was no difficulty. If her husband would imitate her father, their house, with all its poverty, would soon be the house of God and the gate of heaven.

To some extent, Mrs. Bunyan's pleas prevailed. John fell in eagerly with the religion of the times and went with the best of them to church twice a day. He greatly respected and admired the ministers of God; he admired their name, their garments, and their work.

Sundays at Elstow were a strange mixture of levity and seriousness. There were two full services at the church, according to the Book of Common Prayer, and then there were May games, Whitsun ales, Morris dances, and various other sports. In the services and sports, to which the parishioners were summoned by the same church bells, Bunyan was accustomed to take part. He was skilled at ringing the church bells, ready at any time to challenge the whole countryside to a trial of skill at the belfry ropes. One Sunday, having rung the parish into church, he took his place as usual at his wife's side, joining with the congregation in the service and awaiting the delivery of the discourse. The preacher was intelligent and earnest in setting forth the evils of breaking the Sabbath. The sermon did its work. It was meant for him. No more violation of the fourth commandment for John Bunyan. He was determined to obey it from then on with heart and soul. His mind was made up once for all.

This impression, though, proved only to be temporary. Before he had finished eating, he had shaken the sermon out of his thoughts and was prepared to return to the old sports and games with great delight. No sooner said than done. That very afternoon he was on the village green, flinging himself with his usual enthusiasm into a game of "cat." Suddenly, he heard a voice from heaven. He thought for a moment, threw his "cat" upon the ground, and quit playing. He stood like a statue, trembling at the demand of the superhuman voice that he heard ask, "Will you leave your sins and go to heaven, or have your sins and go to hell?" He thought Christ was standing with him face to face, and that He had come to inflict the punishment, which he deserved. Bunyan did not need much time to decide. He heard, he considered, and he decided. He concluded that there could be no other result than that he would be damned for his wicked life, and if it must be so, he might as well be damned for many sins as for one. So back he went to play, not a soul among his companions aware of the astounding processes of thought and feeling which had been going on within him.

His conscience, however, was ill at ease. Mrs. Bunyan was incessant in her prudent endeavors to win him to Christ, and incidents were frequently occurring for which he was rebuked. "You ungodly wretch!" said a woman to him one day, as he cursed and swore and played the fool in the street in his typical manner. "You ungodly wretch! I never heard such swearing in my life. You are enough to spoil all the youth in the whole town." He was put to shame, especially since the woman who had reproved him was known for her own sinful lifestyle. He wished with all his heart that he could be a little child again, and that he might learn to speak without that wicked way of swearing. The rebuke of the woman took effect. He quit swearing and became a reader of Scripture and an outwardly reformed man, both in his words and in his life. His neighbors took notice of the change. They began to speak well of him to his face and behind his back. This gratified him, and he was puffed up. There was not a man in England who could please God better than he. He was all right now, he thought.

Self-denial was required from him, and he religiously took up his cross. He was passionately fond of dancing, and for a full year he still adhered to it, sometimes on the village green and at other times in a building still standing on the green. Now, though, he believed that dancing was unholy, and wishing to be as holy as possible, he gave it up. Old associates entreated him, and the wellknown music tempted him, but he resolved that he would never dance again, and he never did. Another favorite amusement of his was bell-ringing, which some thought was improper in excess or when it deviated from its worthwhile purpose and became a means of amusement. This, he felt, must also be relinquished. After some inward struggles, Bunyan gave this up, too.

As with many who profess mere outward religion, John Bunyan believed that his way was now perfect before the Lord. A notable alteration had come upon his life and manners. He was sure of paradise at last. The improvement was confessedly marvelous. His wife could not contain herself for joy. Her household was becoming like her father's. The marriage portion of the two books was bearing fruit. The Practice of Piety was being embodied in her husband's practice. In The Plain Man's Pathway to Heaven, John was walking right alongside her.

Unhappily, it was all a mistake. The reformed one himself being our witness, he had not passed from death unto life, so as to become a new creature in Christ Jesus. Notwithstanding the change in his behavior, there had been no change of heart. He was still in need of the regeneration of the Holy Spirit.

There are men who have taken issue with Bunyan about his spiritual condition. Some of his biographers have ridiculed and others have resented his claim that he was yet unsaved. They deny that he was either hardened or depraved. They thought that Bunyan must have been having fits of religious fervor and thought himself to be near to God or far from Him based upon his emotional state, and his alienation from his Maker was imaginary and not real.

But the biographers are wrong, and the man of Elstow right. Amendment of the life is not renewal of the nature. However admirable in itself, it is insufficient for salvation. To man at his best, the oracles of God declare, You must be born again (John 3:7). While Bunyan's understanding and explanation of his spiritual condition at that time might have been intense and impassioned, its truth should not be denied. He described his condition accurately. His was the case of the Israelites exactly, who did not know about God's righteousness and seeking to establish their own, they did not subject themselves to the righteousness of God (Romans 10:3). He had a name that he lived, but he was dead (Revelation 3:1).

Bunyan's fundamental sensibility was remarkable. His instincts and impulses were flourishing, if not somewhat domineering. Where his neighbors were unmoved, he was agitated. Where they saw nothing that was unusual, he was either in ecstasies or tears.

This peculiarity must be kept in mind, lest Bunyan's words and actions at this time are thought to be characteristic of all spiritual conversions rather than exclusively to the temperament and characteristics of Bunyan himself. Some people do not seem to show much emotion, while the emotions and passions of others seem to rise and fall as unevenly as ocean waves during a great storm.

Conversion is essential to salvation, but conversion may come without our being so humiliated as to loathe ourselves like toads, as Bunyan described, and without our being so excited as to want to speak of God's love to the very crows that are sitting on the plowed lands. Our new birth may be as certain as was the pilgrim's, although we have never thought, with Bunyan, that the devil was pulling at our clothes and have never been ready with him to swoon with satisfaction at the thought of Christ's compassion for our souls. Every man is affected spiritually according to his temperament. Bunyan was thus affected by the great and strong wind rather than by the still small voice.

And yet, the act of his transition from death unto life was unobserved. There is no specific moment in Bunyan's life when it can be said that he was made a new creation. All his accounts and statements justify the opinion that it was a work of time. He went on, believing that he was pleasing God as well as any man in England, though having incessant regret and sorrow due to his failures in this area. The failures multiplied, and Bunyan regularly alternated between presumptuous self-righteousness and miserable despair.

His Conversion and Profession of Faith

Bunyan's business took him into Bedford one day. A few poor women were sitting at a door as he passed by. He listened to their discussion. They looked like religious women, and he thought that perhaps he might have a chance of joining in the religious talk a practice, as he told his wife, he liked to do now. As he listened, he was amazed. No sermon at Elstow Church had ever informed him of the necessity of the new birth, the treachery of the human heart, the temptations of the wicked one, the grace of the Holy Spirit, or the sovereignty and compassion of God in Christ. The things spoken of by the women struck him with great force. If it was true, then he certainly was lacking in the genuine evidence of a godly man, and what they were saying seemed to be true. The women were simple in their manner and happy. There was such appearance of grace in all they said that their intelligence and sincerity were beyond doubt. God was making Bunyan willing to rejoice in Christ Jesus and to have no further confidence in the flesh.

Bunyan sought the acquaintance of these invaluable helpers. They were cheerfully at his service and did their best to explain to him the way of God more perfectly. Two results ensued: the one, Bunyan's heart softly and tenderly received what the women brought from Holy Scripture; and the other, a great bending of the mind to a continual meditating on the good things of which he heard and read. The Scripture was about to be fulfilled that he should know the truth, and that the truth should make him free (John 8:32), but the process went forward slowly. What right had John Bunyan to say that he had the necessary faith? He had no evidence that he had been elected to salvation. He could not tell that the day of grace was not already past and gone. He answered these temptations as best he could. He wrestled manfully, but every now and then he would almost meet with defeat.

Up to this time he had kept his spiritual turmoil to himself. In time, he described his spiritual situation to those godly women he had met. They answered him as best they could but soon saw the wisdom of introducing him to Pastor Gifford, who could better answer Bunyan's questions and deal with his situation. Nothing better could have happened. Gifford's sensible judgment and larger knowledge brought his new friend's impetuous and prolific imagination under discipline and restraint. Many of his mistakes were subtly corrected, and a sounder habit of apprehending the will of God was gradually found. Mr. Gifford recommended that Bunyan should rely more upon the Word of God and less upon his emotion and imagination.

The immediate result was a renewal of his distress. It seemed to him that he was a most grievous transgressor. The more he meditated, the more he trembled. Bunyan remained strenuous in prayer and steadfast in his study of the Scriptures, hoping against hope. It came to pass that he was sitting in a neighbor's house, very sad, when the word came to him suddenly: If God is for us, who is against us? (Romans 8:31). Soon after, as he was going into the country, that other word came to him, He has made peace through the blood of His cross (Colossians 1:20). Then, while sitting by the fire in his house, another word came to him: Since the children share in flesh and blood, He Himself likewise also partook of the same (Hebrews 2:14).

It would have been better for Bunyan if he had remembered that the comforting words of God were still within his reach. God's Word remained certain and constant, even while Bunyan's emotions continued to rise and fall. The grounds for his consolation in Christ was not his feelings, but the divine assurance that Christ had put away his sins by the sacrifice of Himself.

Bunyan came across a copy of Luther's commentary on the book of Galatians. It was the most well-suited thing imaginable for Bunyan at this time, for Luther was a man who had similar passion and emotional contrasts. No other book was ever so precious to him, except the Word of God. Bunyan's turmoil continued, and it is told in Grace Abounding.

Bunyan's case was a remarkable one throughout. Others should not attempt to imitate it, but we might do well to become much more familiar with the sin and the sinfulness of our own hearts and the exceeding sinfulness of our sin in the sight of God. Bunyan's case ought to cause us to realize, too, how active and strong our adversary the devil is in attempting to keep sinners from the Savior.

Eventually, however, Bunyan found lasting deliverance from self and sin through Jesus Christ. It had been evident to others for a long time that John Bunyan belonged to Christ, and now he was of that mind himself. He could neither specify the moment nor define the act of his transition into life, but he really was alive unto God.

The next thing he realized, as he continued to learn from the divine Word, was the need to confess Christ before men. He accordingly explained to the church his desire to walk with it in the ordinances of Christ. He was cheerfully accepted and, having been baptized, was enrolled in the membership of that church.

About this time he was seized by what seemed to be pulmonary consumption, or tuberculosis. He began to recover and then fell ill again but ultimately fully recovered and became strong. His health having been restored, he diligently carried out the duties of his church membership, rendering effectual help to his pastor in meetings for devotion and in visiting the sick. His ability in these respects was so noticeable that his brethren by common consent made him a deacon of the church and committed to lead in caring for the physical needs of the congregation and the official attention to the poor. Having moved from Elstow to Bedford, he accepted the office of deacon and used it well, earning himself a good reputation throughout the neighborhood. At this time he was a widower, but of the circumstances of his bereavement we have no account.

An entry in the Bedford church book indicates Bunyan's advancement in the esteem of his brethren. "At a meeting held on the 27th of the 6th month, 1657, the deacon's office was transferred from John Bunyan to John Pernie, because he could no longer discharge its duties aright, because he was busily employed in preaching." Some of his fellow members had desired him to speak a word of exhortation to them at their private meetings, and although humbled in spirit at their request, he had consented, and in two separate assemblies had discovered his gifts to them. These exercises confirmed their opinion, and they then invited him to take his turn in their village preachings. His compliance from time to time was so satisfactory that of his call to the ministry, his companions had no doubt.

They reported their opinion to the pastor, who in due time communicated to the church his own belief that they were right. The result was that Bunyan was called forth and appointed to the more ordinary and public preaching of the Word. With great fear and trembling at the sight of his own weakness, he applied himself to the work-not, however, without God's Spirit urging him on and with great encouragement from the Scriptures. He had further encouragement besides, for the country all around came by hundreds to hear the Word. Many confessed and affirmed that they had been awakened by him, so that the Word of God came with much refreshment to his heart.

Suffering for Conscience's Sake

The old inquiry was soon proposed to Bunyan, By what authority are you doing these things? And who gave you this authority? (Matthew 21:23). The answer was at hand. His ability to preach was his authority, especially since a judgment of that ability had been pronounced by the church to which he belonged. With most anxious and prayerful care, his brethren had summoned him to the service, and in that summons he recognized the voice of God. All the ordination that he required, he had thus obtained.

Copyright: Aneko Press