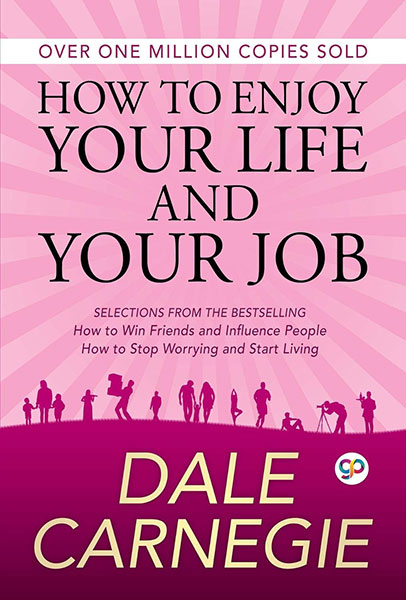

How to Enjoy Your Life and Your Job

How to Enjoy Your Life and Your Job will help you create a new approach to life and people and discover talents you never knew you had. This bestseller shows you how to make every day more exciting and rewarding—how you can get more done, and have more fun doing it. Dale Carnegie's time-tested advice will help you to: • Make other people feel important • Avoid unnecessary tension • Get people to say yes • Turn routine tasks into stimulating opportunities • Smile in the face of criticism A life-changing book that has helped people around the world, 'How to Enjoy your Life and Your Job' is your key to achieving success in your professional and personal life.

BEST DEALS

About the Author

Dale Carnegie (1888–1955) was an American writer and lecturer and the developer of famous courses in self-improvement, salesmanship, corporate training, public speaking and interpersonal skills. He was born in an impoverished family in Maryville, Missouri. Carnegie harbored a strong love and passion for public speaking from a very early age and was very proactive in debate in high school. He went to the Warrensburg State Teachers College and later onwards became a salesman for Armour and Company in Nebraska. He also moved to New York in the pursuit of a career in acting and gave classes in public speaking at the Young Men's Christian Association. During the early 1930's, he was renowned and very famous for his books and a radio program. When 'How to Win Friends and Influence People' was published in 1930. It became an instant success and subsequently became one of the biggest bestsellers of all time. It sold more than 10 million copies in many different languages. He also began work as a newspaper columnist and formed the Dave Carnegie Institute for Effective Speaking and Human Relations, with several branches globally. Carnegie loved teaching others to climb the pillars of success. His valuable and tested advice was used in many domains and has been the inspiration of many famous people's success. One of the core ideas in his books is that it is possible to change other people's behavior by changing one’s reaction to them. The most famous and cited maxims in the book are "Believe that you will succeed, and you will," and "Learn to love, respect and enjoy other people."

Read Sample

Chapter 1 : Find Yourself and Be Yourself: Remember, There is No One Else on Earth Like You

I have a letter from Mrs. Edith Allred, of Mount Airy, North Carolina: “As a child, I was extremely sensitive and shy,” she says in her letter. “I was overweight and my cheeks made me look even fatter than I was. I had an old-fashioned mother who thought it was foolish to make clothes look pretty. She always said: ‘Wide will wear while narrow will tear’; and she dressed me accordingly. I never went to parties; never had any fun; and when I went to school, I never joined the other children in outside activities, or even athletics. I was morbidly shy. I felt I was ‘different’ from everybody else, and entirely undesirable.

“When I grew up, I married a man who was several years my senior. But I didn’t change. My in-laws were a poised and self-confident family. They were everything I should have been but simply was not. I tried my best to be like them, but I couldn’t. Every attempt they made to draw me out of myself only drove me further into my shell. I became nervous and irritable. I avoided all friends. I got so bad I even dreaded the sound of the doorbell ringing! I was a failure. I knew it; and I was afraid my husband would find it out. So, whenever we were in public, I tried to be gay, and overacted my part. I knew I overacted; and I would be miserable for days afterwards. At last I became so unhappy that I could see no point in prolonging my existence. I began to think of suicide.”

What happened to change this unhappy woman’s life? Just a chance remark!

“A chance remark,” Mrs. Allred continued, “transformed my whole life. My mother-in-law was talking one day of how she brought her children up, and she said, ‘No matter what happened, I always insisted on their being themselves.’ … ‘On their being themselves.’ … That remark is what did it! In a flash, I realized I had brought all this misery on myself by trying to fit myself into a pattern to which I did not conform.

“I changed overnight! I started being myself. I tried to make a study of my own personality. Tried to find out what I was. I studied my strong points. I learned all I could about colors and styles, and dressed in a way that I felt was becoming to me. I reached out to make friends. I joined an organization—a small one at first—and was petrified with fright when they put me on a program. But each time I spoke, I gained a little courage. It took a long while—but today I have more happiness than I ever dreamed possible. In rearing my own children, I have always taught them the lesson I had to learn from such bitter experience: No matter what happens, always be yourself!”

This problem of being unwilling to be yourself is “as old as history,” says Dr. James Gordon Gilkey, “and as universal as human life.” This problem of being unwilling to be yourself is the hidden spring behind many neuroses and psychoses and complexes. Angelo Patri has written thirteen books and thousands of syndicated newspaper articles on the subject of child training, and he says: “Nobody is so miserable as he who longs to be somebody and something other than the person he is in body and mind.”

This craving to be something you are not is especially rampant in Hollywood. Sam Wood, one of Hollywood’s best-known directors, said the greatest headache he has with aspiring young actors is exactly this problem: to make them be themselves. They all want to be second-rate Lana Turners or third-rate Clark Gables. “The public has already had that flavor,” Sam Wood keeps telling them; “now it wants something else.”

Before he started directing such pictures as Goodbye, Mr. Chips and For Whom the Bell Tolls, Sam Wood spent years in the real-estate business, developing sales personalities. He declares that the same principles apply in the business world as in the world of moving pictures. You won’t get anywhere playing the ape. You can’t be a parrot. “Experience has taught me,” says Sam Wood, “that it is safest to drop, as quickly as possible, people who pretend to be what they aren’t.”

I asked Paul Boynton, then employment director for a major oil company, what is the biggest mistake people make in applying for jobs. He ought to know: he has interviewed more than sixty thousand job seekers; and he has written a book entitled 6 Ways to Get a Job. He replied: “The biggest mistake people make in applying for jobs is in not being themselves. Instead of taking their hair down and being completely frank, they often try to give you the answers they think you want.” But it doesn’t work, because nobody wants a phony. Nobody ever wants a counterfeit coin.

A certain daughter of a streetcar conductor had to learn that lesson the hard way. She longed to be a singer. But her face was her misfortune. She had a large mouth and protruding buck teeth. When she first sang in public—in a New Jersey night club—she tried to pull down her upper lip to cover her teeth. She tried to act “glamorous.” The results? She made herself ridiculous. She was headed for failure.

However, there was a man in this night club who heard the girl sing and thought she had talent. “See here,” he said bluntly, “I’ve been watching your performance and I know what it is you’re trying to hide. You’re ashamed of your teeth!” The girl was embarrassed, but the man continued, “What of it? Is there any particular crime in having buck teeth? Don’t try to hide them! Open your mouth, and the audience will love you when they see you’re not ashamed. Besides,” he said shrewdly, “those teeth you’re trying to hide may make your fortune!”

Cass Daley took his advice and forgot about her teeth. From that time on, she thought only about her audience. She opened her mouth wide and sang with such gusto and enjoyment that she became a top star in movies and radio. Other comedians tried to copy her!

The renowned William James was speaking of people who had never found themselves when he declared that the average person develops only ten percent of his or her latent mental abilities. “Compared to what we ought to be,” he wrote, “we are only half awake. We are making use of only a small part of our physical and mental resources. Stating the thing broadly, human individuals thus far live within their limits. They possess powers of various sorts which they habitually fail to use.”

You and I have such abilities, so let’s not waste a second worrying because we are not like other people. You are something new in this world. Never before, since the beginning of time, has there ever been anybody exactly like you; and never again throughout all the ages to come will there ever be anybody exactly like you again. The science of genetics informs us that you are what you are largely as a result of twenty-three chromosomes contributed by your father and twenty-three chromosomes contributed by your mother. These forty-six chromosomes comprise everything that determines what you inherit. In each chromosome there may be, says Amram Scheinfeld, “anywhere from scores to hundreds of genes—with a single gene, in some cases, able to change the whole life of an individual.” Truly, we are “fearfully and wonderfully” made.

Even after your mother and father met and mated, there was only one chance in 300,000 billion that the person who is specifically you would be born! In other words, if you had 300,000 billion brothers and sisters, they might all have been different from you. Is all this guesswork? No. It is a scientific fact. If you would like to read more about it, consult You and Heredity, by Amram Scheinfeld.

I can talk with conviction about this subject of being yourself because I feel deeply about it. I know what I am talking about. I know from bitter and costly experience. To illustrate: When I first came to New York from the cornfields of Missouri, I enrolled in the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. I aspired to be an actor. I had what I thought was a brilliant idea, a shortcut to success, an idea so simple, so foolproof, that I couldn’t understand why thousands of ambitious people hadn’t already discovered it. It was this: I would study how the famous actors of that day—John Drew, Walter Hampden, and Otis Skinner—got their effects. Then I would imitate the best points of each one of them and make myself into a shining, triumphant combination of all of them. How silly! How absurd! I had to waste years of my life imitating other people before it penetrated through my thick Missouri skull that I had to be myself, and that I couldn’t possibly be anyone else.

That distressing experience ought to have taught me a lasting lesson. But it didn’t. Not me. I was too dumb. I had to learn it all over again. Several years later, I set out to write what I hoped would be the best book on public speaking for businessmen that had ever been written. I had the same foolish idea about writing this book that I had formerly had about acting: I was going to borrow the ideas of a lot of other writers and put them all in one book—a book that would have everything. So I got scores of books on public speaking and spent a year incorporating their ideas into my manuscript. But it finally dawned on me once again that I was playing the fool. This hodgepodge of other men’s ideas that I had written was so synthetic, so dull, that no businessman would ever plod through it. So I tossed a year’s work into the wastebasket and started all over again. This time I said to myself: “You’ve got to be Dale Carnegie, with all his faults and limitations. You can’t possibly be anybody else.” So I quit trying to be a combination of other men, and rolled up my sleeves and did what I should have done in the first place: I wrote a textbook on public speaking out of my own experiences, observations, and convictions as a speaker and a teacher of speaking. I learned—for all time, I hope—the lesson that Sir Walter Raleigh learned. (I am not talking about the Sir Walter who threw his coat in the mud for the queen to step on. I am talking about the Sir Walter Raleigh who was professor of English literature at Oxford back in 1904.) “I can’t write a book commensurate with Shakespeare,” he said, “but I can write a book by me.”

Be yourself. Act on the sage advice that Irving Berlin gave the late George Gershwin. When Berlin and Gershwin first met, Berlin was famous but Gershwin was a struggling young composer working for thirty-five dollars a week in Tin Pan Alley. Berlin, impressed by Gershwin’s ability, offered Gershwin a job as his musical secretary at almost three times the salary he was then getting. “But don’t take the job,” Berlin advised. “If you do, you may develop into a second-rate Berlin. But if you insist on being yourself, someday you’ll be a first-rate Gershwin.”

Gershwin heeded that warning and slowly transformed himself into one of the significant American composers of his generation.

Charlie Chaplin, Will Rogers, Mary Margaret McBridge, Gene Autry, and millions of others had to learn the lesson I am trying to hammer home in this chapter. They had to learn the hard way—just as I did.

When Charlie Chaplin first started making films, the director insisted on Chaplin’s imitating a popular German comedian of that day. Charlie Chaplin got nowhere until he acted himself. Bob Hope had a similar experience: spent years in a singing-and-acting act—and got nowhere until he began to wisecrack and be himself. Will Rogers twirled a rope in vaudeville for years without saying a word. He got nowhere until he discovered his unique gift for humor and began to talk as he twirled his rope.

When Mary Margaret McBride first went on the air, she tried to be an Irish comedian and failed. When she tried to be just what she was—a plain country girl from Missouri—she became one of the most popular radio stars in New York.

When Gene Autry tried to get rid of his Texas accent and dressed like city boys and claimed he was from New York, people merely laughed behind his back. But when he started twanging his banjo and singing cowboy ballads, Gene Autry started out on a career that made him the world’s most popular cowboy both in pictures and on the radio.

You are something new in this world. Be glad of it. Make the most of what nature gave you. In the last analysis, all art is autobiographical. You can sing only what you are. You can paint only what you are. You must be what your experiences, your environment, and your heredity have made you. For better or for worse, you must cultivate your own little garden. For better or for worse, you must play your own little instrument in the orchestra of life.

As Emerson said in his essay on “Self-Reliance”: “There is a time in every man’s education when he arrives at the conviction that envy is ignorance; that imitation is suicide; that he must take himself for better, for worse, as his portion; that though the wide universe is full of good, no kernel of nourishing corn can come to him but through his toil bestowed on that plot of ground which is given to him to till. The power which resides in him is new in nature, and none but he knows what that is which he can do, nor does he know until he has tried.”

That is the way Emerson said it. But here is the way a poet—the late Douglas Malloch—said it:

If you can’t be a pine on the top of the hill,

Be a scrub in the valley—but be

The best little scrub by the side of the rill;

Be a bush, if you can’t be a tree.

If you can’t be a bush, be a bit of the grass,

And some highway happier make;

If you can’t be a muskie, then just be a bass—

But the liveliest bass in the lake!

We can’t all be captains, we’ve got to be crew,

There’s something for all of us here.

There’s big work to do and there’s lesser to do

And the task we must do is the near.

If you can’t be a highway, then just be a trail,

If you can’t be the sun, be a star;

It isn’t by size that you win or you fail—

Be the best of whatever you are!

To cultivate a mental attitude that will bring us peace and freedom, remember…

Let’s not imitate others.

Let’s find ourselves and be ourselves.

Chapter 2 : Four Good Working Habits That Will Help Prevent Fatigue and Worry

Good Working Habit No. 1

Clear Your Desk of All Papers Except Those Relating to the Immediate Problem at Hand.

Roland L. Williams, President of the Chicago and Northwestern Railway, once said, “A person with his desk piled high with papers on various matters will find his work much easier and more accurate if he clears that desk of all but the immediate problem at hand. I call this good housekeeping, and it is the number-one step toward efficiency.”

If you visit the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., you will find five words painted on the ceiling—five words written by the poet Pope:

“Order is Heaven’s first law.”

Order ought to be the first law of business, too. But is it? No, the average desk is cluttered up with papers that haven’t been looked at for weeks. In fact, the publisher of a New Orleans newspaper once told me that his secretary cleared up one of his desks and found a typewriter that had been missing for two years!

The mere sight of a desk littered with unanswered mail and reports and memos is enough to breed confusion, tension, and worries. It is much worse than that. The constant reminder of “a million things to do and no time to do them” can worry you not only into tension and fatigue, but also into high blood pressure, heart trouble, and stomach ulcers.

Dr. John H. Stokes, professor, Graduate School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, read a paper before the American Medical Association—a paper entitled “Functional Neuroses as Complications of Organic Disease.” In that paper, Dr. Stokes listed eleven conditions under the title: “What to Look for in the Patient’s State of Mind.” Here is the first item on that list:

The sense of must or obligation; the unending stretch of things ahead that simply must be done.

But how can such an elementary procedure as clearing your desk and making decisions help you avoid this high pressure, this sense of must, this sense of an “unending stretch of things ahead” that simply have to b done? Dr. William L. Sadler, the famous psychiatrist, told of a patient who, by using this simple device, avoided a nervous breakdown. The man was an executive in a big Chicago firm. When he came to Dr. Sadler’s office, he was tense, nervous, worried. He knew he was heading for a tailspin, but he couldn’t quit work. He had to have help.

“While this man was telling me his story,” Dr. Sadler says, “my telephone rang. It was the hospital calling; and instead of deferring the matter, I took time right then to come to a decision. I always settle questions, if possible, right on the spot. I had no sooner hung up than the phone rang again. Again an urgent matter, which I took time to discuss. The third interruption came when a colleague of mine came to my office for advice on a patient who was critically ill. When I had finished with him, I turned to my caller and began to apologize for keeping him waiting. But he had brightened up. He had a completely different look on his face.”

“Don’t apologize, doctor!” this man said to Sadler. “In the last ten minutes, I think I’ve got a hunch as to what is wrong with me. I’m going back to my office and revise my working habits. … But before I go, do you mind if I take a look in your desk?”

Dr. Sadler opened up the drawers of his desk. All empty—except for supplies. “Tell me,” said the patient, “where do you keep your unfinished business?”

“Finished!” said Sadler.

“And where do you keep your unanswered mail?”

“Answered!” Sadler told him. “My rule is never to lay down a letter until I have answered it. I dictate the reply to my secretary at once.”

Six weeks later, this same executive invited Dr. Sadler to come to his office. He was changed—and so was his desk. He opened the desk drawers to show there was no unfinished business inside of the desk. “Six weeks ago,” this executive said, “I had three different desks in two different offices—and was snowed under by my work. I was never finished. After talking to you, I came back here and cleared out a wagonload of reports and old papers. Now I work at one desk, settle things as they come up, and don’t have a mountain of unfinished business nagging at me and making me tense and worried. But the most astonishing thing is I’ve recovered completely. There is nothing wrong anymore with my health!”

Charles Evans Hughes, former Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, said: “Men do not die from overwork. They die from dissipation and worry.” Yes, from dissipation of their energies—and worry because they never seem to get their work done.

Good Working Habit No. 2

Do Things in the Order of Their Importance.

Henry L. Doherty, founder of the nationwide Cities Service Company, said that regardless of how much salary he paid, there were two abilities he found it almost impossible to find.

Those two priceless abilities: first, the ability to think. Second, the ability to do things in the order of their importance.

Charles Luckman, the lad who started from scratch and climbed in twelve years to president of the Pepsodent Company, got a salary of a hundred thousand dollars a year, and made a million dollars besides—that lad declared that he owed much of his success to developing the two abilities that Henry L. Doherty said he found almost impossible to find. Charles Luckman said: “As far back as I can remember, I have gotten up at five o’clock in the morning because I can think better then than any other time—I can think better then and plan my day, plan to do things in the order of their importance.”

Frank Bettger, one of America’s most successful insurance salesmen, didn’t wait until five o’clock in the morning to plan his day. He planned it the night before—set a goal for himself—a goal to sell a certain amount of insurance that day. If he failed, that amount was added to his next day—and so on.

I know from long experience that one is not always able to do things in the order of their importance, but I also know that some kind of plan to do first things first is infinitely better than extemporizing as you go along.

If George Bernard Shaw lad not made it a rigid rule to do first things first, he would probably have failed as a writer and might have remained a bank cashier all his life. His plan called for writing five pages a day for nine heartbreaking years, even though he made a total of thirty dollars in those nine years—about a penny a day. Even Robinson Crusoe wrote out a schedule of what he would do each hour of the day.

Good Working Habit No. 3

When You Face a Problem, Solve It Then and There If You Have the Facts Necessary to Make a Decision. Don’t Keep Putting Off Decisions.

One of my former students, the late H.P. Howell, told me that when he was a member of the board of directors of U.S. Steel, the meetings of the board were often long-drawn-out affairs—many problems were discussed, few decisions were made. The result: each member of the board had to carry home bundles of reports to study.

Finally, Mr. Howell persuaded the board of directors to take up one problem at a time and come to a decision. No procrastination—no putting off. The decision might be to ask for additional facts; it might be to do something or to do nothing. But a decision was reached on each problem before passing on to the next. Mr. Howell told me that the results were striking and salutary: the docket was cleared. The calendar was clean. No longer was it necessary for each member to carry home a bundle of reports. No longer was there a worried sense of unresolved problems.

A good rule, not only for the board of directors of U.S. Steel, but for you and me.

Good Working Habit No. 4

Learn to Organize, Deputize, and Supervise.

Many businesspersons are driving themselves to premature graves because they have never learned to delegate responsibility to others, insisting on doing everything themselves. Result: details and confusion overwhelm them. They are driven by a sense of hurry, worry, anxiety, and tension. It is hard to learn to delegate responsibilities. I know. It was hard for me, awfully hard. I also know from experience the disasters that can be caused by delegating authority to the wrong people. But difficult as it is to delegate authority, executives must do it if they are to avoid worry, tension, and fatigue.

Executives who build up big businesses and don’t learn to organize, deputize, and supervise usually pop off with heart trouble in their fifties or early sixties—heart trouble caused by tension and worries. Want a specific instance? Look at the death notices in your local paper.